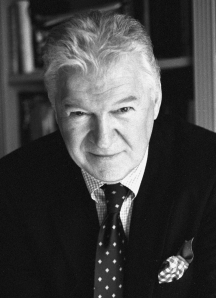

Described by NPR as “the most eloquent man in the world,” writer and broadcaster Frank Delaney has interviewed more than 3500 of the world’s most important writers over three decades, but it’s now his turn to be interviewed by Lynne Nolan for the Dublin Writers Festival.

Frank Delaney has clinched top prizes across a variety of formats, judged literary prizes including the Booker and created passionate documentaries on many subjects including George Bernard Shaw, Oscar Wilde, Emily Dickinson, Robert Frost and James Joyce. Re:Joyce, his weekly podcast series, has made Joyce’s Ulysses accessible to readers across the globe, as it deconstructs, examines and illuminatesthe mighty novel line-by-line. On New Year’s Day, 2014, it registered its millionth download and currently downloads at the rate of approx. 1200 per day.

Born and raised in Tipperary, Connecticut-based Delaney spent more than 25 years in England before moving to the US in 2002, where his first ‘American’ book, Ireland, became a New York Times Bestseller. His work includes the recent trilogy, Venetia Kelly’s Travelling Show, The Matchmaker of Kenmare, and The Last Storyteller, as well as the novels Tipperary and Shannon.Since 2006, he has published five ‘Novels of Ireland,’ all addressing, decade by decade, the 20th century history of his homeland.

Q&A:

With the Storytellers project on the internet, you offer a series of short stories produced as e-books called with introductions preceding each story, leading the reader to understand the history and craft behind the creation of myth.What inspired you to take this approach?

Among the many great remarks that writers have made about writing, one that stays high in my mind came from Vladimir Nabokov. “The writer,” he said – and he meant, principally I think, the novelist – is three things: a Magician; a Storyteller; a Teacher.We’re entitled as readers to take “Storyteller” as a given. “Magician” becomes the obvious aspiration, but writerly ambition embodies dangers – your reputation shouldn’t be any of your business: your job is to do excellent work. While letting readers decide which of Nabokov’s trio they find in my books, I’m happy to settle for the “Teacher” slot. Thus, the Storyteller series, conceived as an experiment to test this new e-book delivery system, gave me a good opportunity to, as it were, teach without teaching.

After writing your first piece, a novella named ‘My Dark Rosaleen’, you followed it up at the rate of a novel almost every year. What got you hooked?

In a word, storytelling. Since childhood I’ve wanted to be a novelist – so that I could tell stories! I’ve always relished the power of the tale, how it grabs us and then absorbs us, and casts a spell over us, and teaches us. Stories in all forms – anecdotes, joke-stories, shaggy dog stories, story poems, narrative paintings, narrative poems – I’m a sucker for them all, and have always been. Then I found that I was having an exciting (if slightly alarming) number of ideas for novels, stories, plays, films – every one a story told one way and another. So – “only connect the passion with the prose and both shall be exalted” and even though E.M. Forster also said, “Oh, dear me, yes, the novel tells a story” (or words to that effect) he himself was no mean storyteller. I used to get so alarmed at writers and critics who dismissed novels as “storytelling” and then, when I relaxed, I saw that (a) those who dismissed narrative weren’t themselves very good at it; and (b) most of our greatest literature is narrative.

What have you been working on recently?

I’ve just delivered to my agent a new novel, The Holy Wolf. It’s set in Ireland in 1872, and in the 6th century; it’s centered on a boy’s school (with the ruined abbey nearby) where a wolf has been attacking the students. Except that there hadn’t been wolves in Ireland for more than a hundred years.

What are your three favourite books by Irish writers, and why?

On another day, at another time, this list would change, according to mood, sunshine and general atmosphere. It would, however, have one constant, Ulysses, for about 260,000 reasons (that’s the number of words in the novel). Number two would probably be How the Irish Saved Civilisation by the Irish-American writer, Thomas Cahill, a short and brilliant tour d’horizon of our brilliant past and its contribution to the world. If that’s disallowed on the grounds of birthplace I’d opt for Dr. Joe Lee’s Ireland 1912-1985, the best of our history books. And then I’d add all the collected short stories of William Trevor. Tomorrow, though, that list will change – except for Joyce.

With your podcast series Re:Joyce, you’ve made James Joyce’s Ulysses accessible to people across the globe. How big an undertaking has that project been for you and did you expect it to be as popular as it has been?

It’s a bigger undertaking than most people could imagine – but I did go into it with my eyes open. It requires significant work almost every day because I produce, essentially, a mini-essay every week that would, if written, amount to somewhere between 1200 and 1500 words, and they have to be based on interrogation of the text and the researches necessary to support that effort. The researches are multiple and multi-faceted, but a total delight. And no, I did not expect one million downloads and a further 110,000 in the first months of this year – and I did not expect listeners as far flung as the 20,000 in Australia, the thousands and thousands up and down the wetsern seaboard of North America, the sole listener in Uzbekhistan, the couple in Algeria – and so on. Nor did I expect the height of the learning curve: doing what I do to make this podcast every week has become an academy.

When did you first read Ulysses, and what appealed to you about it, do you have a favourite scene or episode?

Like many people of my generation I had always had a troubled relationship with Joyce – principally because we were told with such vehemence not to read him. And then we couldn’t acquire his books when we went looking. In fact I found my first copy on the 16 Bus in Dublin – an American tourist had left it behind in a brown paper bag. (I wonder if it’s accurate that the novel was never banned in Ireland – no need to, it’s alleged, because no bookseller would stock it.) I read it and read it, and had the usual difficulties that others report, but I kept returning to it and found that it came alive when I read it aloud. Then, in 1981, the centenary of Joyce’s birth loomed. I was working at the BBC in London and it seemed apparent that I would be asked to make radio and television programmes about him. So I went to the novel again with a more determined will, and I loved it and loved it – so much that my own first book, published in 1981,was James Joyce’s Odyssey –a Guide to the Dublin of Ulysses which, to my astonishment, became a bestseller in Britain and the U.S. As to favorite scenes – today it’s the National Library conversation; tomorrow it may be the Ormond Hotel; or the cabman’s shelter; or Mr. Deasy’s school; or Davy Byrne’s. And so on.

Of the documentaries you’ve made about great writers, which did you most enjoy working on?

How can I choose? Joyce, obviously; and a long radio documentary about Yeats; a documentary for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation on Erskine Childers and The Riddle of the Sands (it won an award which is probably why I’m so fond of it); Norman Mailer for his 60th birthday; the New England poet, Robert Frost; Henry James; Robert Louis Stevenson (I’ve just put up as an e-book Jim Hawkins and the Curse of Treasure Island, my faithful sequel to Treasure Island); Oscar Wilde (multiple broadcasts); a long radio documentary on George Bernard Shaw; television programmes on Stephen King, Tom Clancy, Jane Austen – I’ve always deliberately gone for the widest possible “brow” because I have such a suspicion of snobbery, especially the literary kind, and I’ve always had the best time working in this arena.

What words of wisdom would you offer to up-and-coming writers?

Oh, hell! Who should advise anybody? Yet, in a collegial spirit, for three years on the Internet I tweeted a Writing Tip every day (#ByTheWord) which attracted so wide a following (and still does) that I may make a book of them. Therefore the best way that I can answer your question is to give you the first ten of them – and remember on Twitter they have to make not more than 140 characters;

Always finish your work session in the middle of a sentence.

Make drawings or little effigies of your main characters.

Establish on a separate page your story’s calendar.

Give your readers what they expect but not in the way they expect it.

Would you recognize your main characters if you saw them on the street?

Never begin successive sentences with the same word – unless for tension and style.

Most plots are: Boy meets Girl, Boy loses Girl, Boy wins girl back.

Avoid the verb “to be”: it does nothing.

Do an adjective count at the end of each session and halve the number.

Use little description of your characters – let the reader do it.

And if after that you still want to write – then you’re probably a natural and you’ll have a rich time!

To learn more about Frank Delaney and his work you can visit his website or find him on Twitter.

Reblogged this on Portfolio.

i’ve listened to all re joyce pod.s and here, i’ve discovered another frank. the frank frank rather than the most generous, professor frank, franking it out 10 minutes a week on ulysses.

a fellow joycean in admiration of finnegans wake. the true JAJ opus.